A

compulsive obsessive desire to ignore the lessons of history is slowly choking

us.

If

Tasmania is to become a renewable energy powerhouse, shouldn’t we have some

understanding how existing wind farms and the Basslink interconnector work, who

profits and who pays?

What’s

the difference between regulated and unregulated interconnectors and what are

the ramifications of the termination of the Basslink Services Agreement

announced on 10th February, an agreement covering an interconnector

that was supposed to have a life of 60+ years but is falling apart after only

15 years.

Without

stopping to analyse what went wrong with Basslink we seem to be careering ahead

to build an even more expensive one, whilst the State refuses to face up the

underlying fiscal sustainability of a government which is gradually falling behind in attending

to its core functions.

At

the centre of energy policy is a Minister who is the shareholder minister in charge

of Hydro, TasNetworks and the retailer Aurora Energy, and who pretends he is

able to seamlessly resolve any conflict between competing parties whilst also looking after the interest of renewable energy proponents, consumers and Tasmanian

taxpayers.

If

it sounds too good to be true that's because it is.

Basslink

profitability

We’re

on the brink of having another interconnector foisted upon us but neither the

government nor Hydro Tasmania are prepared to tell us the profitability of the

existing Basslink cable. The annual report tells us the quantity of electricity

imported and exported but that’s it. How much money is made from the importing

and exporting? Given the proposed Marinus cable will have three times the

capacity of Basslink it would be useful to know. All we know from Hydro’s

annual report is that it’s becoming harder to make money. Budget forward estimates suggest lower

profits in the future from Hydro.

The

info which the government/Hydro prefers wasn’t discussed is all publicly

available. Both AEMO, the Australian Energy Market Operator and AER, the

Australian Energy Regulator publish masses of data. AEMO manages the NEM, the

National Electricity Market and strives to recover costs from all participants.

AER has a monitoring and enforcement role and perhaps most significantly sets

network prices. OTTER, the Office of the Tasmanian Economic Regulator sets

retail prices and has a regulation and monitoring role in the wholesale market.

OTTER

publishes the $ value of Basslink imports and exports weekly. Here’s an example,

covering NEM week 52 from 19th to 25th December 2021.

Exports

for the week were 18.33GWh and imports 40.32 GWh. The $ revenue was $481,280

from exports and $1,469,350 from imports giving total revenue of $1,950,630 for

the week.

Over

the 52 weeks from 28th Jun 2020 to 26th June 2021, NEM

reported total BL exports of 1,021 GWh and imports of 1,612 GWh. (NB Hydro’s

2021 Annual Report reported BL exports of 1,007GWh and imports of 1,612 GWh for

the financial year 2020/21. The minor difference in the export figure is almost

certainly due to the financial year being a slightly different period from the

52 weeks covered by the NEM figures).

The

revenue (or inter regional revenue as it’s more correctly called) from BL for

the 52-week period was $42 million from exports and $31 million from imports,

for a total of $73 million for 2020/21. That implies exports averaged $41 per

MWh and imports $19 per MWH.

To

understand what this means a bit more background is needed.

The

BL interconnector, owned and operated by Basslink P/L but currently in

receivership, generates revenue in a similar way to

generators in the NEM, by bidding into the spot market its capacity to deliver

energy, with the returns determined by the price difference and the energy

flows between Victoria and Tasmania. These returns are the inter-regional

revenues. Under the arrangement with Hydro pursuant to the Basslink Service

Agreement (BSA), Basslink as the owner/operator of the interconnector agreed to

swap the inter-regional revenue for an agreed fixed facility fee, plus

performance-related payments covering availability adjustments and commercial

risk sharing. The agreement also gave Hydro the rights to control the way in

which Basslink bids its interconnector capacity, either flowing in or flowing

out of Tasmania.

On 10th February Hydro decided to terminate the BSA.

Minister Barnett implied the recent lengthy arbitration proceedings which

determined the cable was unable to perform as required, led to the termination

decision. But there was likely much more to the story than that. (More about this

can be found below in the section Termination of BSA).

Even though the BSA has now ended it is useful to understand how

it worked. Basslink P/L receives a weekly payment from NEM representing a

week’s worth of inter-regional revenues. Inter- regional revenue, whether from

exports or imports is a net figure. In the case of exports, Basslink P/L buys

electricity from a Tasmanian generator (almost certainly Hydro) and sells it

into the Victorian market. NEM will collect the sale amount, pay the Tasmanian

generator for the purchase and remit the balance being the inter-regional

revenue to Basslink P/L.

Under the BSA, Basslink P/L then forwarded the inter-regional

revenue to Hydro and Hydro paid Basslink P/L the facility fee plus the

performance adjustments each month. The inter-regional revenues were legally earned

by Basslink P/L, as operator of the cable, but were included as Hydro’s income pursuant to the BSA

arrangement. Basslink P/L included the facility fee as income and paid all the

operating expenses associated with the interconnector.

Hydro also pays Macquarie Bank a monthly fee which represents

costs incurred by Hydro when it was sweettalked into a hedging arrangement with

Macquarie Bank to protect it from interest rate rises during construction of

the link and from interest rates embedded in the facility fee. Rates have since

plummeted. The hedging arrangements adds roughly another 50 per cent to the

facility fee which means Basslink currently costs Hydro about $125 million per

year. That is confirmed by the Basslink current liabilities of $125.8 million

listed in Hydro’s books as at 30th June 2021. A current liability is

one expected to be paid in the next 12 months.

Hence Hydro has needed to earn a lot extra to pay the fees. As

we have seen total inter-regional revenues for 2020/21 were $73 million. This

is before the losses from transmission over the BL cable of approx 3 per cent

plus another 1 per cent when electricity is converted from alternating AC to

direct DC at the beginning of transmission and vice versa at the other end of

the cable. Total transmission losses are estimated to be about 5 percent which

means Hydro probably made $70 million from BL trading in 2020/21. Hydro’s

financials recorded expected inter-regional revenues as financial assets. The

amount listed as a current asset, in other words expected in the next 12

months, was $64 million for the 2020/21 year. The actual inter-regional revenue

received for 2020/21 was likely to have been $70 million. With costs of $125

million, that’s a big loss.

Money is made importing and exporting. The precondition for making

profits are the different spot prices in Tasmania and Victoria.

The following table shows the average quarterly spot prices since

1st July 2020.

|

Average

quarterly spot prices |

|

|||

|

NEM

quarters |

Unit:

$/MWh |

|||

|

|

VIC |

TAS |

Difference |

|

|

2020 Q3 |

July 20 to Sept 20 |

54 |

51 |

3 |

|

2020 Q4 |

Oct 20 to Dec 20 |

40 |

46 |

-6 |

|

2021 Q1 |

Jan 21 to March 21 |

27 |

34 |

-7 |

|

2021 Q2 |

Apr 21 to June 21 |

77 |

47 |

30 |

|

July 21 to Sept 21 |

64 |

27 |

37 |

|

|

2021 Q4 |

Sept 21 to Dec 21 |

33 |

30 |

3 |

Note:

The NEM year is a calendar year

The

table is just a snapshot of average spot prices each quarter. There is a lot of

variation within quarters, from day to day and from hour to hour. Care need to

be taken when drawing conclusions. But where Vic spot prices are well in excess

of Tas spot prices as occurred in 2021 Q2 and Q3, electricity will be exported

to Vic. The exports in 2021 Q2 for instance, only represented 17 per cent of BL

flows (both export and import) for Hydro’s 2021 year but they earned 38 per

cent of inter-regional revenue for the year. The pattern continued for the next

quarter 2021 Q3, covering July to Sept 2021 (the first quarter of Hydro’s 2022

year).

The

earlier two quarters in the 20/21 year (2020 Q4 and 2021 Q1) saw Tas spot prices

exceeding spot prices in Vic. This led to more imports during those quarters,

accounting for 30% of inter-regional revenue for 20/21. Imports and exports for

the rest of 20/21 weren’t significant in $ terms. The following table has the

figures, prices and quantities, for inter-regional revenue.

|

NEM quarters |

Exports |

Imports |

|||||

|

|

Amount GWh |

Value $m |

Av per MWh $ |

Amount GWh |

Value $m |

Av per MWh $ |

|

|

2020

Q3 |

July

20 to Sept 20 |

287 |

6.5 |

23 |

332 |

5.3 |

16 |

|

2020

Q4 |

Oct

20 to Dec 20 |

180 |

5.7 |

32 |

461 |

11.2 |

24 |

|

2021

Q1 |

Jan

21 to Mar 21 |

111 |

1.7 |

15 |

577 |

10.4 |

18 |

|

2021

Q2 |

Apr

21 to June 21 |

444 |

28.2 |

63 |

242 |

4.0 |

16 |

|

2021

Q3 |

July

21 to Sept 21 |

581 |

33.1 |

57 |

173 |

3.1 |

18 |

|

2021

Q4 |

Oct

21 to Dec 21 |

383 |

8.8 |

23 |

285 |

7.4 |

26 |

Just

to reiterate, the revenue figures are not the gross revenue received, but

rather the differences between the spot prices in Vic and Tas. Basslink P/L buys in one market and sells in

the other. NEM pays it the difference each week. In the case of exports, it’s

the extra earned by exporting to Vic compared to selling on the spot market in

Tas.

Going

back to the table of average spot prices, another striking feature is the low

Tas spot price in 2021 Q3 from July to Sept. As the Australian Energy Regulator

AER noted in its quarterly report, this was the lowest quarterly price for any

of the five NEM regions since 2012. (NB The regions are Tas, Vic, NSW, Queensland

and SA). The low figure was probably caused by favourable rains over winter and

spring in the northern and western rivers in Tas and the increased electricity

from wind with Cattle Hill and Granville Harbour wind farms now fully

operational. The additional wind capacity which has doubled Tasmania’s

electricity from wind from 10 to 20 per cent of our needs, will likely put

downward pressure on Tas spot prices and make importing electricity a less

attractive proposition. Hydro power can reasonably comfortably supply the other

80 per cent.

The latest AER quarterly report covering July to Sept

2021 also noted spot prices declined in every NEM region. There was a record number of negative prices in

every region. In Victoria prices were negative 22% of the time. Under NEM

rules, wholesale prices can fall as low as negative $1000 a megawatt-hour,

meaning in theory generators have to pay to deliver power into the spot market.

Prices generally fall into the red around the middle of the day when wind and

solar generators and coal power plants are competing to dispatch their energy.

There’s not much point sending electricity into a market with negative prices

but stopping and restarting generators can be even more costly. One of the

market responses to negative prices is to instal batteries with the aim of

withholding electricity from the market and waiting for a better price. This is

now occurring on the mainland. Many will remember then Treasurer Scott Morrison

pooh-poohing Tesla’s large battery proposed for South Australia back in 2017:

“"I mean, honestly, by all means have the world's

biggest battery, have the world's biggest banana, have the world's biggest

prawn like we have on the roadside around the country, but that is not solving

the problem.”

People making investment decisions disagreed. Batteries are

becoming more widespread, even being proposed to run alongside aging coal-fired

generators hoping to get a few more years of use before they go the way of

dinosaurs. Batteries will tend to lower price variations, the very thing which has

made exporting to Vic via Basslink a profitable (at times) activity for Hydro.

Lower spot prices and smaller differences between Tasmanian

and Victorian prices were looking likely to impact Hydro’s profits. The forward

estimates in the Budget papers showed payments from Hydro to the government (income

tax equivalent payments and dividends) declining in real terms.

A doubling of electricity from local wind generators has

already lessened the opportunities to import electricity profitably, and the

increasing use of batteries on the mainland will lessen the opportunities to export

electricity profitably. That’s been Hydro’s dilemma. Casting a giant shadow

over Hydro was another 10 years of Basslink where costs of $125+ million per

annum would have coincided with inter-regional revenues of about $70 million

per annum, but under increasing pressure. Some of the shadow may have been

removed with the decision to terminate the BSA. (More on this below in the last

section headed Termination of the BSA.)

Paradoxically the Marinus interconnector would likely make it

even harder to profit from the arbitrage advantages that arise when spot prices

in Tasmania and Victoria differ. By its very nature a regulated interconnector will

reduce arbitrage advantages that may exist between NEM regions as the costs and

benefits of a regulated connector and are spread across all network users. Diminished

arbitrage advantages across the network are inevitable.

One doesn’t expect Hydro or the government to shout about

Basslink’s unprofitability from the rooftops. But the kneejerk response to

claim commercial-in-confidence at every turn rather than assist the

understanding of publicly available information is a step too far in a world

where the peddling of falsehoods is becoming the norm rather than the

exception.

As we will see below, another reason the government and its

electricity businesses don’t want to dwell too much on the financial lessons of

Basslink is because they see themselves building a completely new electricity

system for the 2030s. TasNetworks’ new Chair Roger Gill made this clear during

the December 2021 Leg Co scrutiny hearings. Planning for the future is

commendable but that shouldn’t mean ignoring past lessons. If Tasmania is going

to produce twice as much energy as it needs surely some understanding of how

trading via the current interconnector works, what are the problems and how

will the new electricity system make it better.

Regulated vs non-regulated interconnectors

There are currently three major interconnectors in the NEM…..

Basslink, Murraylink and Directlink.

Basslink,

at 370km long, is the world’s second

longest subsea electricity interconnector with a nominal capacity to export 594

MW from Tasmania to Victoria, and import 478 MW. It cost $874 million to build and

was commissioned in April 2006. It’s owned by Basslink P/L a subsidiary of

Keppel Infrastructure Fund listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange and part

owned by the Singapore Government. Basslink P/L is currently in Receivership

looking for new owners. Basslink is part of NEM but is an unregulated link.

On the other hand,

both Murraylink and Directlink are regulated interconnectors. Both started as

unregulated links but swapped because life was too difficult. Both were

unviable as unregulated links. Becoming regulated means spreading the costs

amongst a wider number of network users.

Basslink P/L was not a

true MNSP Merchant Network Service Provider, as unregulated links are often called,

because of the exclusive arrangement with Hydro which entailed the payment of

an agreed facility fee which removed most of the trading risks from Basslink

P/L. Murraylink and Directlink didn’t have sugar daddies when trying to survive

as unregulated interconnectors. Basslink is about to experience what life is

like without a regular facility fee.

Prices that can be

charged by regulated interconnectors are determined by AER, the Australian

Energy Regulator. This is no different to TasNetworks’ transmission and

distribution networks, both of whose prices are regulated by AER via price

determinations every five years.

Murraylink is an interconnector between

South Australia and Victoria. approximately 176 kms long, rated at 220MW and

commissioned in 2002 at a cost of $177 million. It is currently owned by Energy Infrastructure Investments Group EII, but

operated by APA. The ownership of EII is

split between APA with 19.9%, Japan-based Marubeni Corporation with 49.9%, and Osaka Gas with 30.2%. APA is an ASX listed company which has

recently bought $99 million worth of Basslink P/L’s debt, for a price likely to

have been less than the face value of the debt, but which gives APA a seat at

the table when discussing future ownership of Basslink with the Receivers.

The

main transmission service providers in each region are ElectraNet in SA and

AusNet Services in Vic. How the system of regulated interconnectors work can be

gleaned from AER’s determinations The following cut and paste from page 10 of Murraylink determination discusses the expected

impact of the regulated price for the Murraylink interconnector on residential

electricity bills.

The annual electricity bill for customers in

each region in the national electricity market will reflect the combined cost

of all the electricity supply chain components – wholesale generation costs,

transmission and distribution network costs, the retailers’ costs and profit

margin, and the cost of environmental policies including subsidies for

renewable energy, such as solar feed-in tariffs. The transmission network

charge component of electricity bills for SA and VIC represent about 9 per cent

of an average customer's annual electricity bill in SA and about 6 per cent in

VIC.

Murraylink’s

network charges are built into transmission charges in SA and VIC. The main

transmission service providers in each region (ElectraNet in SA and AusNet

Services in VIC) take a portion of Murraylink’s allowed revenue in developing

the applicable transmission charges to apply to and collect from customers in

their respective regions. Murraylink is then compensated by ElectraNet and

AusNet.

Murraylink

is a small component of the broader transmission networks that serve SA and

VIC. This small proportion explains the modest impact this final decision on

Murraylink is likely to have on average annual electricity bills in SA and VIC.

Murraylink’s

value as determined by AER for price setting purposes, it’s RAB or Regulated

Asset Base, is around $120 million. What it may have cost to build ($177

million) is irrelevant. AER determines a price based on what it reckons the

asset is worth. For comparison purposes TasNetworks’ transmission RAB is valued

at $1,287 million and its distribution assets at $1,737 million. In simple

terms AER allows providers to make returns on regulated assets after allowing

for expected expenses including capital upgrades. The current returns are

around 5 per cent pa. Distribution costs are between three- and four-times

transmission costs

In

the case of Murraylink the value of the link is only $120 million. Hence there

is not a huge impact on electricity prices in Vic and SA, the two connected

States. As AER noted:

The

transmission network charge component of electricity bills for SA and VIC

represent about 9 per cent of an average customer's annual electricity bill in

SA and about 6 per cent in VIC.

Directlink

is a smaller interconnector designed to link northern NSW with southern Queensland,

59 km in length and commissioned in 1999 at an estimated cost of US$70 million

with a total rating of 180 MW. Directlink’s RAB is currently about $145 million.

Directlink

is also owned by EII, the same as Murraylink. APA is the operator. Given that

APA has indicated it sees Basslink’s future as a regulated interconnector, it

wouldn’t be hard to visualise Basslink with the same owners as Murraylink and

Directlink, and all operated by APA. The termination of the BSA makes this

possibility much more likely. Basslink will struggle to survive as an

unregulated asset, just as Murraylink and Directlink did, now that Hydro has

stopped propping it up with the monthly facility fee.

When

Basslink becomes a regulated asset, the AER will assess the value of its RAB

which will determine how much will be paid to Basslink’s new owners. This

amount will be recovered from network users in the same way as for Murraylink,

described above. The issue for Marinus is whether agreement can be reached to

enable Marinus’ costs to be recovered for all net work users. At this stage

other States aren’t keen for their electricity users to fork out for Marinus

Meanwhile

Marinus is not the only new interconnector on the NEM drawing board. Humelink a

proposed interconnector in NSW is facing the same hurdles as Marinus. These

were laid out in detail by Bruce Mountain, Ted Woodley and Hugh Outhred in a recent article in Renew Economy.

Specifically

the authors said:

Those in favour of projects in the Report (AEMO’s

2021Transmission Cost Report) and in the Integrated System Plan (ISP)

invariably suggest that AEMO’s inclusion of such projects amounts to an

endorsement of their economic benefit.

However, AEMO’s ISP is a system-wide expansion

study in which committed generation projects are taken as inputs.

This means that in the assessment of HumeLink, for

example, since Snowy 2.0 is deemed to be committed, the ISP treats this as a

sunk cost.

But of course Snowy 2.0 and HumeLink are

intertwined complements. Like a train station and a train line, the one has

much less value without the other. Treating one as “committed”, biases

the decision to commit the other.

To address this, in evaluating the economic merit

of HumeLink, it is therefore essential to include the cost of Snowy 2.0.

AEMO does not do this – as explained Snowy 2.0 is treated as a committed

project and so its costs are ignored in the ISP’s analysis of HumeLink.

This means that AEMO’s analysis can not conclude that

HumeLink is an economically sensible transmission expansion, it can only

conclude that having ignored the costs of Snowy 2.0, its model finds that

HumeLink is necessary in order to not waste the storage potential of Snowy 2.0.

This fundamental modelling issue is not widely

understood. It is important that it is, since the inclusion of projects

such as HumeLink in AEMO’s ISP is treated by influential but distant actors –

such as parliamentarians – as credible proof of endorsement.

Considering the importance of AEMO’s position on

power system development, it is essential that AEMO states more clearly the

basis upon which major augmentations such as HumeLink and Marinus Link are

included in its development plans, and how the economic merit of such inclusions

should be understood.

The case for Marinus stacks up, so

we’re told, because there’ll be 200 per cent of renewables looking for a market.

At the same time the case for 200 per cent renewables makes sense because there’ll

be a 1500 MW cable ready to transport electricity to mainland markets. Marinus

is needed so we’re told, to be able to export all the surplus wind power, which

coincidentally is only being built to take advantage of Marinus. It’s an

intellectually dishonest, self-fulfilling circular proposition.

If the 200 per cent renewables

projects and Marinus were considered as one project requiring a viability

assessment before proceeding, they wouldn’t be built. It would have already

happened if they were viable.

Instead we have a system, a

conspiracy of subterfuge, which is the only way that otherwise uneconomic

projects can proceed. This system is supported by two other dodgy factors. The

first of those is being able to ignore a range of costs by treating them as

sunk costs and therefore not relevant when assessing project viability. The

second is being able to have the relevant assets accepted as regulated assets thereby

guaranteeing participants guaranteed income over a longer period. That’s the

prize being sought. Any public policy errors are papered over with sunk costs

and guaranteed income streams.

Both Murraylink and Directlink were

nonviable as unregulated assets. They both needed to become regulated and have

all network users help give them a return.

On the matter of sunk costs, it mustn’t

be forgotten that being categorised as such doesn’t mean they don’t have to be

paid. It only means they can be ignored when assessing project viability.

Basslink had sunk costs. The Expert Panel which reported on Basslink in March 2012

explained how the $50 million deposit paid by Hydro when Basslink was being

built and all the hedging arrangement entered into during constructions were

treated as sunk costs and ignored when assessing the project viability. Yet Hydro

is still paying the $150+million of construction hedging arrangements incurred

prior to 2003. These are included in the monthly fee paid to Macquarie Bank .

They may be sunk costs but they still impact Hydro’s cash flow.

A grand plan or a hotpotch of

competing interests?

The major problem with providing

promoters an opportunity to treat project costs as sunk costs is that it

encourages aberrant behaviour. If that’s not moral hazard on steroids then what

is? If a viable project results, it will be by good luck rather than sound

planning. The authors of the Renew Economy paper further explain the problems

with projects like Marinus:

The fundamental commercial driver for transmission

companies is to maximise revenues through building more regulated assets.

Hence, there is an inherent incentive to underestimate costs to get a project

to the proposal stage.

History bears this out. We are unaware of any

transmission project where the cost decreased after the initial estimate.

Naturally, a project develops momentum as it

progresses, and it becomes more difficult to stop, even with the inevitability

of escalating costs and decreasing (even negative) net benefits.

Estimated costs need far more scrutiny, right from

the initial stages of a proposal, and some form of reprimand when shown to be

understated.

History certainly does bear this out. Basslink at

$874 million cost double its original estimate. And that figure doesn’t include

the $150+ millions of sunk costs conveniently overlooked.

Having assets that will be regulated is the key. Regulated

returns where costs are borne by all network users is a big attraction.

Marinus’ major proponent, TasNetworks is beastly

careless how much Marinus will cost as it won’t have to fund it. Any addition

to its RAB is always welcome as it means more guaranteed income which all

network users will pay.

TasNetworks’ position highlights the inherent conflicts

between all parties…. the government, Hydro as the major generator, TasNetworks

as the transmission company, private investors hoping to step in and build more

generation assets to reap the rewards of guaranteed income streams and

consumers looking for lower prices. It is highly unlikely that the conflicts

will be satisfactorily resolved as the Minister in charge in is Guy Barnett,

someone who is yet to come across a problem that wasn’t the fault of his

political opponents, and every proposed solution is disingenuously described as

being in the best interest of all Tasmanians. And by the way, there’s no such

thing as a subsidy. Anything that gives a return can’t be a subsidy if evidence

given by Mr Barnett to the recent parliamentary hearing into government

electricity businesses is any guide.

However, we are starting to see conflicts play out.

TasNetworks has received grants to explore/justify

Marinus’ viability knowing it won’t have to fund it and knowing that any

increase in its RAB with more on-island transmission assets will be given a

regulated price by AER which will enable it to get the necessary funds from

Tascorp to construct the assets. Abundant moral hazard rarely leads to sound

public policy decisions.

The government insisted Hydro sign a power purchase

agreement PPA with the Granville Harbour Windfarm. Hydro was obviously

unimpressed because it lists the subsidy given to Granville as a Community

Service Obligation alongside support for Cricket Tasmania and the Hobart

Hurricanes. Why would Hydro as a generator be interested in subsidising another

generator? It makes a semblance of sense for a retailer like Aurora Energy to

enter into PPA with a windfarm like it did with Cattle Hill, but to insist

Hydro as a generator do so suggests heavy handed meddling by the government.

The PPA between Hydro and the Woolnorth Wind Farm

WWF signed to facilitate the 2014 sale of 75 per cent of WWF to Shenhua , a

Chinese State-owned company (Hydro retains the remaining 25 per cent) disguises

an ongoing subsidy to WWF. In its latest reporting year, the 2020 calendar

year, WWF received a $14.66 million subsidy from Hydro for purchases of

electricity and an estimated $15 million for the purchase of large scale

renewable energy certificates LGCs . That’s a total of $30 million. The cash

dividend for the year received by Hydro from WWF was only $4 million. Hence

Hydro’s 25 per cent share in WWF produced cash losses of $26 million. Then

there’s the non-cash effects. At the end of the 2020 reporting period WWF

listed the future benefit of the deal to sell LGCs to Hydro as being worth $96

million. That means there must be a corresponding liability in Hydro’s books of

a similar amount. It’s included in Hydro’s onerous contracts which were listed

as a liability totalling $240 million at 30th June 2021. Different

accounting rules apply to the treatment of LGCs and electricity purchases. The

former are financial assets and need to be valued at fair value each year. The

expected value is recorded as an asset (or liability) and any movement recorded

in the P&L each year. Electricity purchases on the other hand are recorded

when the purchase occurs. Hence expected subsidies of future electricity

purchases aren’t recognised until electricity is delivered. Now $96 million,

the estimated future subsidy to WWF via LGC purchases (NB the agreed purchase

price is greater than the expected market price of LGCs. Hydro will make future

losses buying LGCs from WWF at an agreed price and on-selling them in the

market for less) may not be a particularly large figure but in balance sheet terms

it’s 5 per cent of Hydro’s equity. It also means Hydro’s interest in WWF which

is listed as being worth $71 million, actually has a negative value of $25

million. Heaven forbid if Senator Abetz ever finds out his electricity bills

are subsidising the Chinese government. (More info on WWF’s PPA is presented

below in the section Who will benefit?)

It’s all very well to say an onerous contract was

not onerous at the time it was signed but risk managers should have pointed out

the problem that if a PPA does become onerous and requires Hydro to find cash,

it is likely to occur at the same time as Hydro will itself be feeling cash

flow pressures. As Hydro reaches into its pockets to satisfy the onerous

contracts it will likely find there’s less cash there for the exact same

reasons as caused the PPA to become onerous, viz a fall in electricity spot and

LGC prices. A double whammy. Government policy of propping up other generators via

PPAs can only ever undermine Hydro. It is little wonder Hydro is under

increasing pressure. Governments encouraging others to feast at Hydro’s table

looks like a dumb idea.

That didn’t stop the government from giving public

support to Twiggy Forrest’s desire to buy a sizable chunk of Hydro’s electricity

for his proposed hydrogen plant, possibly as much 20 per cent of Hydro output

which is around 9,000 GWh pa, at a giveaway price of $20 per MWh, as was

reported by ABC reporter Emily Baker. .If Hydro

could otherwise sell the power for $45 per MWh that amounts to a subsidy of $25 per MWh. 2,000 GWh means the subsidy amounts to $50 million pa. Fortunately,

Hydro seems to have resisted government demands to subsidise Twiggy to that

extent. Hydro’s Ian Brooksbank was reported as saying Hydro’s role in

supporting the possible hydrogen industry in Tasmania would be via the

provision of a “firming” service, to fill the gaps which may occur with the

erratic nature of electricity from wind. To not have resisted would have meant Twiggy

would have eaten most of Hydro’s lunch, a dumb idea given its unique suite of

assets.

All the

above serves to emphasise that there are a host of conflicting interests in the

electricity space which Minister Barnett tries to pretend can all be satisfied

by the 200 per cent renewable target/Battery of the nation/Marinus/ hydrogen/Jobs

jobs jobs/lower prices leaving everyone being better off. It’s a silly notion.

There will be winners and losers who need to be identified before we reach the

point of no return, which the campaign of misleading information and unsubstantiated

assertions appears designed to achieve before people realise the full

implications of the grand plan.

Who will

benefit?

The

government’s 200 per cent renewable energy goal will require more wind farms

plus a new connector. It may be useful to have a closer look at a current wind

farm operation and at Basslink to understand where money comes and goes. The

publicly available financial statements for WWF, which produces about 1,000 GWh

pa or about 10 per cent of our needs, and for Basslink P/L, the owner operator

of Basslink (currently in Receivership) are an essential starting point to

understanding the $s involved.

First

let’s look at WWF. The latest financials are for the calendar year ending 31st

Dec 2020. The following is the profit and loss statement:

A healthy

profit of $132 million is evident in the latest year, not bad for a company

with net assets of $264 million. Most of the profits are attributable to subsidies

from Hydro. Specific items needing a closer look are sales revenue, operating

expenses, and fair value gains.

This is

the breakup of sales revenue:

Energy

sales relates to electricity. Environmental energy products are large scale

generation certificates LGCs. Both are covered by PPAs with Hydro.

In the

2020 year WWF produced 1,036 GWh of electricity. 2019 was a windier year

producing 1,205 GWh (These figures are from NEM figures posted on Wiki). This

suggests LGCs are bought at a contracted price of around $46 per LGC. (NB One

MWh creates one LGC meaning one GWh produces 1,000 LGCs and 1,000 GWh produces

1,000,000 LGC. LGC prices have fluctuated between about $20 and $90. Currently

they are in the low $30s).

In the

case of electricity sales, the revenue fall over the 2 years is quite striking.

From approx $75 per MWh to $33 per MWh. These are the gross amounts obtained by

selling through NEM. These aren’t the

net amounts that WWF end up with after the PPA agreement with Hydro. To work

out the net amount one needs to look at the breakup of operating expenses. This is the relevant snapshot:

As can be

seen in the 2019 year WWF paid $33 million to Hydro as a result of the PPA, and

in 2020 it received $14.6 million (the receipt is shown as a negative expense).

That

means, in net terms, WWF received $57 million in 2019 and $49 million in 2020,

round about $46 per MWh in each year. When the market price is below that

figure Hydro pay WWF. When the reverse occurs, WWF pays Hydro. That’s how PPAs

work.With more wind coming on line, spot prices will likely fall meaning Hydro

will be subsiding WWF until the deal expires in 2028.Ouch.

Altho’

both electricity and LGCs are covered by a PPA they are treated differently in

the financial statements. Electricity sales are treated just like any goods and

services are treated by any business. Sales are recorded at the time of sale.

Any possible future subsidy is ignored. There is not sufficient certainty as to

the amount of the future subsidy. The actual subsidy only becomes apparent at

the time of sale. This is why the power purchase agreements with major

industrials in Tasmania which accounts for almost half of Hydro’s total sales

(in quantity terms) do not appear as onerous contracts in Hydro’s books The

sales of electricity to major industrials are recorded at the time of sale and

no provision is made in the financials for possible future contracted

subsidies. (altho’ they may be indirectly included when generation assets are

valued based on future income.)

LGC’s on

the other hand are financial assets. A PPA which includes financial assets need

to be valued each year for accounting purposes. The future expected subsidy to

be received for LGCs needs to be estimated. Changes over a year are recorded as

fair value changes in the P&L, with the value at the end of the year included in the

balance sheet as an asset. In 2020 WWF included $106 million as a fair value

gain for the year. This was the change in the fair value of LGCs for the year.

At the end of 2020 WWFs financial asset re LGCs was recorded as $96 million.

This represents what WWF expects to receive from Hydro for LGCs over and above

the market price. In other words, the expected future LGC subsidy from Hydro.

From

Hydro’s viewpoint it records a similar figure as a liability, viz the value of

the onerous contract with WWF.

In 2020

the subsidy re electricity was $14.6 million. This was actually paid. In the

case of LGCs the subsidy was also paid and included in LGC sales of $47.9

million. It is likely to have been approx $15 million for the year.

Hence the

PPA with WWF meant Hydro subsidised WWF to the tune of $30 million for the

year. That’s to produce roughly 1,000 GWh or 10 per cent of Tasmania’s annual

needs. How much will it cost in subsidies if the 200 per cent renewable target

is reached?

The

operating expenses detailed above indicates the relatively small level of operating

expenses, the flow on costs which spruikers of projects often use to hype their

projects. Consultant/contractor costs are $11 million. This will comprise both

labour and materials. The local component will only be a fraction of this. In

the case of employee expenses, they totalled $4.4 million in 2020. But WWF

reported to ASIC there were only 6 employees. The only conclusion is that they

earned on average $750k for the year. They’re unlikely to be locals paying

Tasmanian payroll taxes and drinking at the pub in Smithton.

The flow

on benefits from wind farm operations are relatively small. Most wind farms are

either owned by foreigners or interstate investors (in the case of Granville) so

income ends up in their hands after bankers grab whatever is owing to them.

The meagre

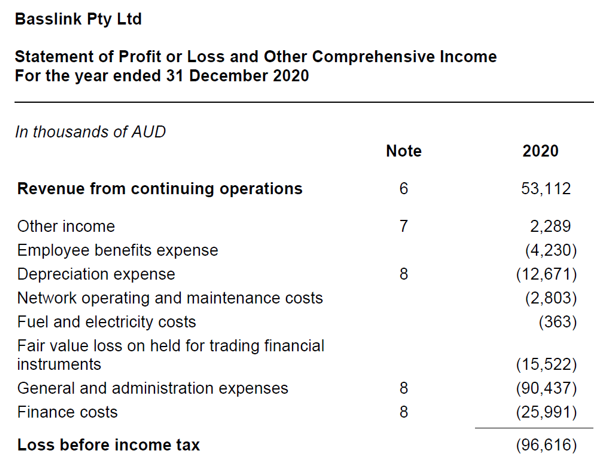

benefits that trickle down from interconnector businesses are similar to

windfarms. Take a look at Basslink’s latest P&L:

This is

the year that recorded the costs of Basslink’s legal outcomes with Hydro. There

are lots of non-recurring entries.

The loss of

$96.6 million highlights BL’s problems which led to a Receiver being appointed

BL had to

write off $30.8 million in facility fees which it had previously included as

income, but Hydro had refused to pay following the 2015/16 cable outage. The

revenue was accordingly reduced from $84 million to $53 million.

General

& admin costs of $90 million include all the compensation payable to Hydro and

the State of Tasmania (not all was paid during the year), plus BL’s legal

costs.

Fair

value losses of $15.5 million and finance costs of $26 million relate to the

costs of Basslink Groups’s finance costs for the year.

Operating

outlays were minor. Network and maintenance costs were $2.8 million and employee

costs were $4.2 million. There were 21 employees, so they averaged $200k each

pa. Not too bad if you can’t get a job at WWF. A few may have been locals. The trickle-down

effect into the local economy wouldn’t have been much more than from a neighbourhood

milk bar. The downstream effects of windfarms once built are negligible.

There’s little there for locals. Absentee owners bankers and other paper

shufflers snaffle most of the lucre.

There’s

absolutely no reason for thinking the downstream effects of a new

interconnector and a landscape full of windfarms will produce a different

result. Saving the planet provides a very convenient camouflage for the self-interests

of a few.

Termination

of the Basslink Services Agreement BSA

On the 10th

February Hydro put out a media release:

Hydro Tasmania confirms it has terminated the Basslink Services

Agreement (BSA) as announced by the Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction

today.

Hydro Tasmania remains willing to discuss with receivers an alternative

commercial model that could include key elements of the BSA, that would provide

funding during the receivership and help transition the asset to an alternative

commercial model.

Consistent with this Hydro Tasmania has made a good faith offer to the

Receivers for an interim arrangement, under which the key elements of the BSA

would be put back in place for one month whilst the parties discuss possible

alternative arrangements.

The Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction’s

announcement on the same day said:

Consistent with the Tasmanian Government and Hydro

Tasmania’s decision in November last year to protect and progress Tasmania’s

legal rights in relation to the Basslink cable, Hydro Tasmania has taken

another step in that process terminating the Basslink Services Agreement (BSA).

This follows the 2020 arbitration concerning the

cause of the 2016 major Basslink outage, which found in the State and Hydro

Tasmania’s favour, confirming the link cannot meet the capacity requirements

set out in the BSA and that the owner of Basslink should pay compensation to

the State.

Since November last year, Hydro Tasmania along with

the State, has been in negotiations with the receivers of Basslink regarding an

alternative commercial arrangement.

The termination of the BSA will not impact

Tasmania’s energy security, which remains on firm footing, with very strong

hydro storage levels, the Cattle Hill and Granville Harbour wind farms, while

the cable will remain in service.

The Tasmanian Government and Hydro Tasmania will

continue to engage with Basslink's financiers and receivers on alternative

commercial arrangements, suitable for the receivership period.

Tasmanians can be assured that our energy security

is stronger than ever and that the Government will continue to act in the best

interests of Tasmanians.

Lat’s try

to make sense of this:

The actual

default by BL which gave Hydro room to terminate the BSA is not clear…..

whether it was the arbitrator’s findings about the cable’s shortcomings or

due to the appointment of a receiver or because the Receiver intends to sell

the cable to another party, it’s not clear. All may be grounds for default by

BL which then allowed Hydro to quit the agreement.

With the

termination of BSA, BL’s Receivers will retain the ongoing inter-regional

revenues IRR and Hydro will cease paying the facility fee.

In most

months the IRR is less than the facility fee so Hydro will be better off.

BL will

continue to buy Hydro’s electricity if it wishes to export but the profits from

the deal will belong to BL. Likewise electricity will still be imported by BL.

It is not

clear what will happen to the arrangements with Macquarie Bank MBL currently

costing about $4 million per month. Part of what Hydro pays MBL each month

relates to the sunk costs incurred pre 2003 so no doubt they will still need to

be paid, but part relates to the hedging arrangements re the interest rate component

of the facility fee. If the facility fee ceases to be payable what happens to

the facility fee swap arrangement with MBL? Another lawyers picnic?

The

Basslink Group owes financiers approx. $640 million. It’s actually not on BL’s

books, rather it’s owed by an associated company called Premier Finance Trust

Australia. What is on BL books is an interest swap arrangement designed to

hedge interest rates on the Group’s borrowings. Interest rates have fallen so

the latest fair value of the hedging arrangement shows a further liability of

$162 million. That’s an estimate of the amount needed to quit the hedging deal.

BL also

has a liability of $23 million labelled Provision for decommissioning costs,

which is an estimate of the costs needed to clean up at the end of the cable’s

life.

Another of

BL’s liabilities is the amount still due to the Tasmanian government of approx.

$50 million following successful legal action.

There is

also a $50 million deposit paid by Hydro to BL back in 2003 which was to be offset

against the facility fee payable from 2029 onwards. If the fee is no longer

payable, what happens to this deposit?

The

messiness of BL’s financials suggests it is unlikely that anyone will buy the

company as a way to acquire the cable. Instead, what will likely happen is the cable

itself will be sold.

The BSA

had another 10 years to run at the time it was terminated. At that time BL’s

income was via the facility fee from Hydro of approx. $85 million pa, which gave

BL an EBITDA (earnings before interest

tax depreciation and amortisation) of roughly $50 million . With the facility

fee being government guaranteed the earnings multiple may have been as high as

10 times giving BL (or at least the cable) a value of $500 million.

However

with the termination of the BSA, the cable’s income will be the inter-regional

revenue and that is a riskier proposition which further means a lower earnings

multiple will be needed to calculate the cable value. If the IRR is estimated

to be $70 million pa, that makes the EBITDA $35 million. Applying a 7 times

earnings multiple gives the cable a value of $245 million.

The

termination of the BSA means the cable is now an unregulated asset without a

guaranteed monthly facility fee which means it’s value could fall by as much as

50 per cent.

By

terminating the BSA Hydro will also have given up any pre-emptive rights it may

have had to acquire the cable should it be sold. But because it (and the Tasmanian

government) are still owed money by BL, it still has a place at the negotiating

table to discuss BL’s future.

For the

cable to become a regulated asset a new owner will have to be found. It’s

likely APA will be involved. It doesn’t make much sense for Hydro to have a

share. That only made sense if the BSA remained intact for another 10 years,

and Hydro ended up paying the facility fee to itself.

It would

make more sense if TasNetworks ran BL, but it is hellbent of trying to get Marinus

to the start line.

Whatever the value of the cable for the new

owner, its likely Regulated Asset Base RAB will end up being roughly similar

once the cable becomes a regulated asset. That in turn will underpin how much the

new owner will receive as a regulated asset.

Which

still leaves the big unknown….. how will Marinus be regulated? How much and who

will pay? It is likely that whatever

Marinus ends up costing, if the estimated cost is currently $3.5 billion, the

final cost will be well in excess of that figure, how much will the value of

its asset base be for the purposes of determining the cost burden on all

network users. The RAB figure will be far less than the cost, that’s for sure.

Which means that much of Marinus’ cost will be immediately written off. It’ll

be reminiscent of Tas Irrigation which builds water infrastructure. Using a

very rough rule of thumb, for every $3 spent on new works, $1 is recouped from

the sale of water rights, $1 of value remains on TI’s balance sheet being the

value of the asset which earns money from water rights holders each year and $1

is written off. In the case of TI there are arguably spill over benefits (forgive

the bad pun) from building new water infrastructure. The growth of industries

which benefit from the new water justifies the community’s investment in an

asset which loses 33 per cent of its value as soon as it is built.

For

Marinus the picture won’t be anywhere near as rosy. The likely spin off

benefits of Marinus and new wind farms, as shown above by examining the affairs

of existing wind farms and interconnectors are likely to be considerably less.

For a State facing momentous fiscal challenges it would be reckless to spend so

much for the benefit of so few.

What is

quite extraordinary is that the latest BL financials cheerily expected the BSA

to last until 2072. But barely a few months later, the cable may only be worth

25 per cent of its original $875 million cost, after a mere 15 years of life.

Yet we

are contemplating doing the same again, going down the same path, without the

slightest interest in learning any of history’s many lessons.

(updated 21st Feb to correct a typo)

Good article John. Can I suggest writing an Executive summary for those that don't have the time or patience to read the entire article?

ReplyDeleteIt's like someone turning on the light. I'll need to read it again (and again) but it fills all the gaps in my understanding of the smoke-and-mirrors stuff the 200% TRET contains.

ReplyDeleteIs the system too complicated? Are politicians responsible for that? Who said keep it simple stupid?

ReplyDeleteWe have Basslink cable, Battery of the nation cable proposed at huge cost & gas pipeline in Baltic sea fractured, maybe by sabotage. Plenty of solar waiting to be harvested. Then there is concentrated solar to harvest too with heliostats.

As Europeans pay massive energy bills in winter we could put PV on our rooftops for maybe one or two years of those energy bills.